Objective: the present participle (or, an early morning letter for the chronic insomniac)

Are you awake as I am?

I jog my memory in reverse before I head to bed, in the way you decelerate the treadmill before you step off. I assume this precaution is to prevent sudden shock. Though I will admit, right here to you, that I have never remembered to do so. In fact, I never want to, as if I’m taking masochistic delight in the muscle spasms, the ankle tension that continues into the week.

Yeah, you could have eased out, been met with a lighter degree of pain. But you think: if it’s pain regardless (and it is) fuck it if I don’t meet it in extreme.

In fact, when I was younger, I’d dance—I mean really dance, all limbs, floorboard stomping dance—each night before bed. Then I’d fall onto my bed, force my body into expedited physical sedimentation, and hold my heart in my ears. The sound of being alive is deafening.

I realize silence is preferred for sleep. But if you’re here, you’re probably not looking to do much of that. Since it’s just you, me, and other early morning fist-clenchers, I’ll tell you that I can’t sleep because I am reading, but I can’t read because it hasn’t been easy. Like sleep, it begs a certain mild octave or monotony of sound. You can’t read against the choir. And yet, reading is often like watching a choir: a desperate corralling of various stimuli. Your eye wanders incessantly; you know there is a source of melody and there are many moments when one specific voice registers, but it’s always slippery, each mouth is moving and you can never quite pin it.

In any case, I am fortunate to be afforded at least some days of quietude and reprieve. I have the choice to live those days underwater while with confidence that the surface is right above my head. I know for many, maybe you, life is instead a perennial blaring—like a deviant echo left over from a once harmonious hum—like you hit down on your crash/ride, but lacked the authority to grab it with the tip of your fingers, so the cymbal suspended as it is, vibrates endlessly around the moon, and then the sun.

And you are this cymbal, tethered to a stand, rooted in the ground, caught in a place feverishly at service to a symphony that you feel you are often at discord with. But you also realize (you must), that a symphony will appear whenever you deem something as music. And you want so, so bad, to deem everything as music. You think: yes, a choir takes two, but a choir came from khorós, Greek for dance—you dance alone, 10 minutes before bed—so there it is: your symphony, your song, your ride, your crash.

But most days you’re cowardly, sheepish, and plain tired. Those days, you’d rather be knocked off your stand, strapped onto two hands, and be cauterized by the intensity of your own friction. No authority, no grasp, no care if it ever becomes music. You just want to be handled, held, made into music, or remain discordant—you don’t care.

You start thinking about Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers, you play Moanin’ and watch the world’s crash/ride sequence: the source of light rides out, the black expanse crashes in.

Now: it’s two hours into the new day, about four years with your insomniac self and your respite is still without consonance. It’s neither song nor rhythm, and you stop searching for the energy to dance or hum. Well, I am here too, stationary but active, picking at my book, swimming in my notes, some of which I’ll share with you. These notes form a rhythm of their own: about staying asleep, staying awake, staying alert, and staying responsible in the use of language.

If you’d like—and I’d like it very much—send me a note from your book. Or just email me back a picture of what’s in front of you. The dust collected in the crack between the wall and your bed, a screenshot from your phone. Anything can be read—a collected choir, just between you and me.

Rocking in lockstep with you, to sleep or somewhere else,

WZ

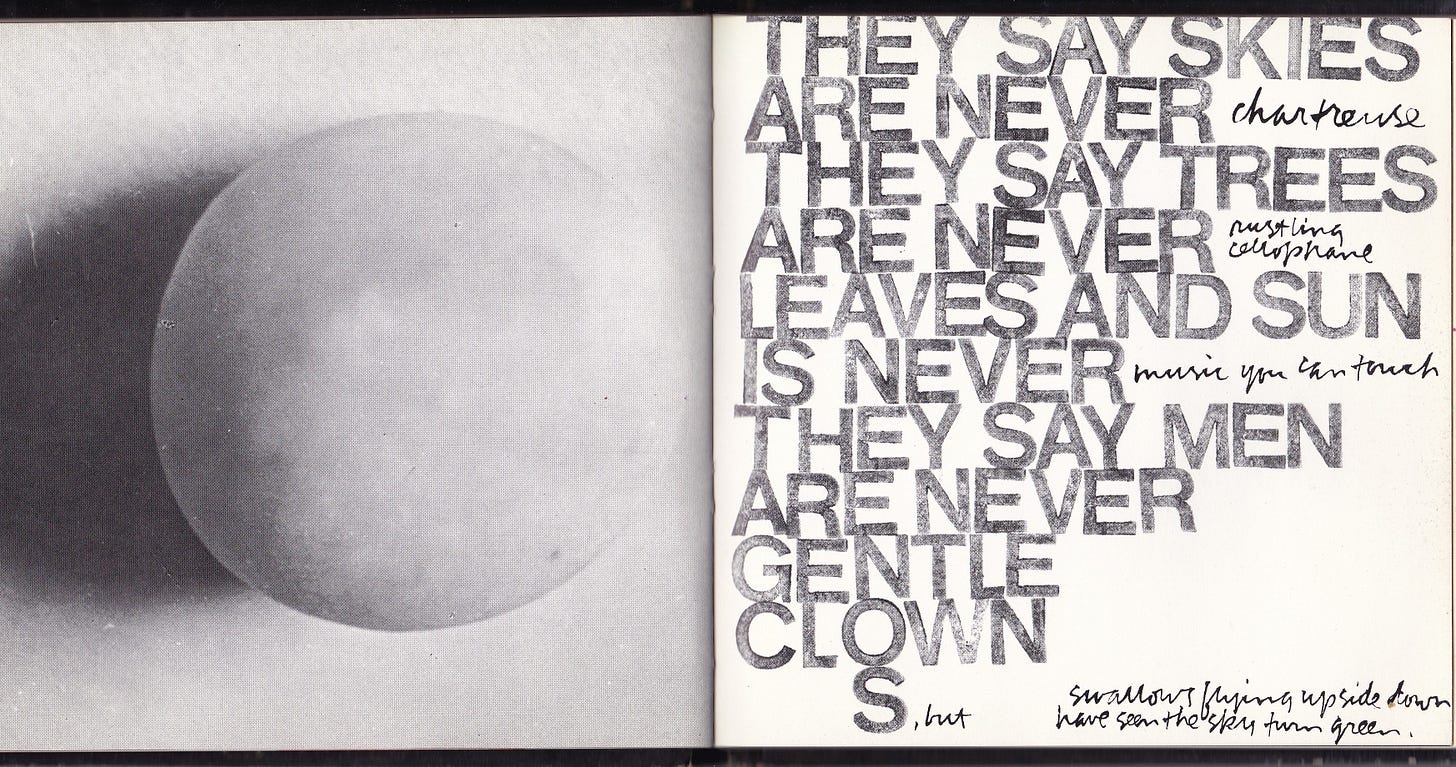

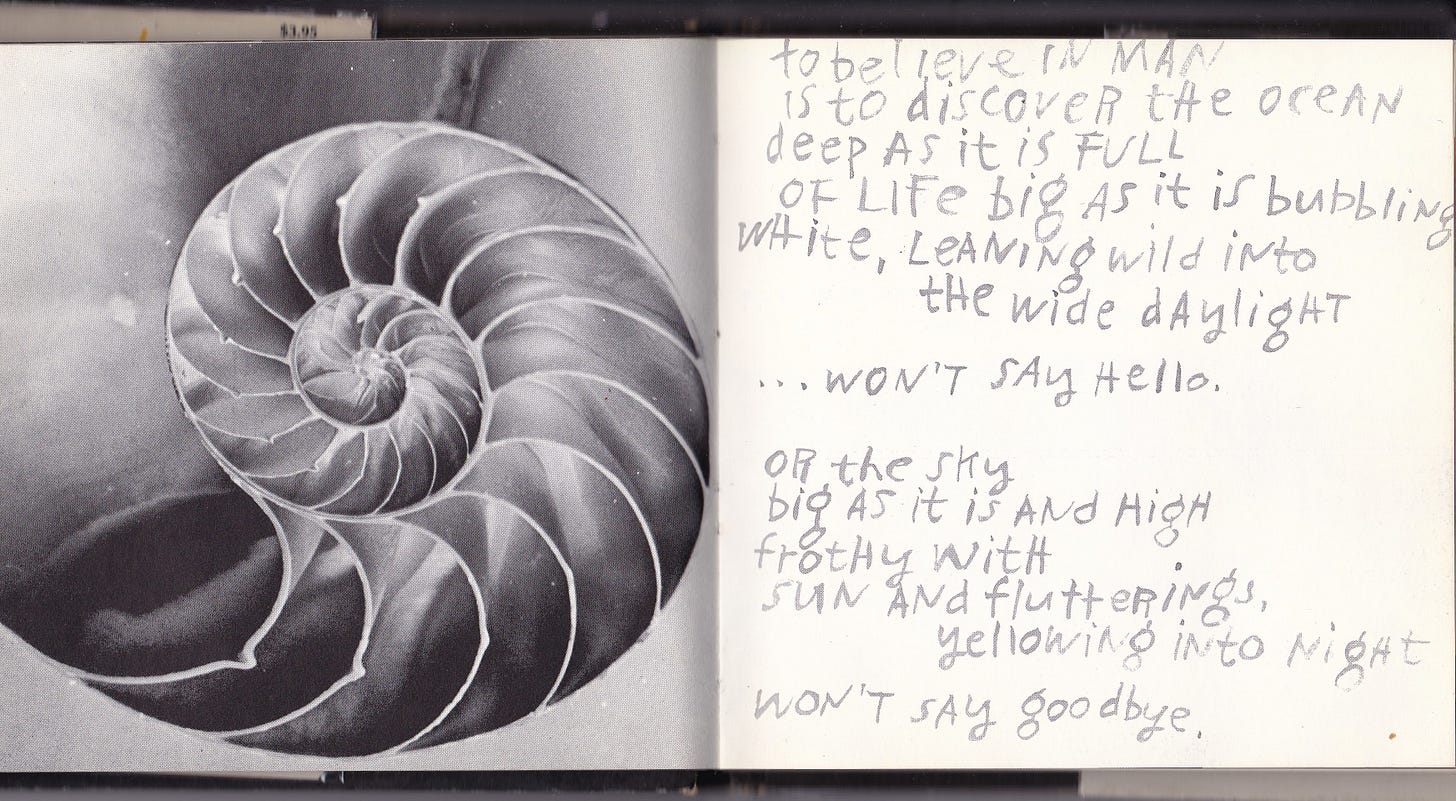

From “to believe in man” by Joseph Pintauro and Corita Kent

“You are no more than an eye. A huge, steady eye that sees everything, your limp body as well as yourself, the beholder beheld, as if it had turned completely round in its socket and without uttering a word was gazing on you, your inside, our dark, empty, sea-green, startled, helpless inside. It looks at you and pins you down. You will never stop seeing your-self. You are unable to do anything, you are unable to escape yourself, you are unable to escape your gaze, you will never be able to: even if you managed to fall asleep so deeply that no shock, no summons, no searing pain could wake you up, there would still be this eye, your eye, which will never shut, which will never fall asleep. You see yourself, you see yourself seeing yourself, you watch yourself watching yourself Even if you woke up, your vision would abide, identical, unchangeable. Even if you managed to accumulate thousands or thousands of thousands of eyelids, there would still be, behind them, this eye to see you. You are not asleep, but sleep will not return again. You are not awake and you will never wake up again. You are not dead, and not even death could bring you deliverance.”

(George Perec, “Between Sleep and Walking’ from The Paris Review Issue 56, Spring 1973)

Excerpts from Citizen, by Claudia Rankine